In Liveness, Auslander discusses authenticity at length within the frame of rock ideology. Speaking with Jenn last week, we started thinking about what authenticity is in the theatre.

Thinking about authenticity in the realm of visual art is somewhat straightforward. At the precise moment when I perceive it, is the painting the real, original work of art as created by the painter? While it may not look the same as when it was first painted – paintings undergo changes at the hands of UV radiation, light, temperature changes, humidity, vandalism, etc. – it is fundamentally the same cultural object.

Benjamin identifies a painting’s authenticity as “the essence of all that is transmissible from its beginning, ranging from its substantive duration to its testimony to the history which it has experienced” (Section II – “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”). The fact that the painting has endured x years, and the physical evidence of its existence throughout these years (cracked paint, decay, sun bleaching, mold, or whatever it may be) are important contributors to its authenticity. What other factors populate the continuum between these two main contributors is unclear – Perhaps imperceptible physical changes, such as changes in chemical composition might lie on this continuum. Or perhaps events that took place near the painting that left no physical evidence (an argument, a repositioning of the frame) might also lie here.

As I understand him, for Benjamin the authenticity of a painting gives it authority, which creates the work’s aura.

In Auslander’s discussion of rock authenticity, things work a little differently. Authenticity is still fundamentally this idea of being ‘the real deal,’ but mapping this idea onto music plays out differently as we cross mediums.

According to Auslander, authentic rock music is created by musicians who work their way up from the bottom, playing in dingey clubs and ‘paying their dues’ in this way. The music itself is created to challenge or protest against the majority opinion. And of course, the musicians display significant proficiency in the live performance of their music. Negotiating rock music in the recording arts and rock music in live performance, Auslander argues that live performance serves to authenticate recorded music to rock fans – Seeing the artists play the music live proves to us that they can actually play it, and most likely played it in the recording. If they can exhibit consistent musical proficiency in live performance, why would they not have played in the recording? (Auslander describes this very situation happening with two separate girl groups, one on the road touring and one recording in studio under the other’s name – But I suspect this is an exceptional occurrence, especially with the increasing union of celebrity iconography and the music business.)

Here, being ‘the real deal’ (authentic to rock ideology) in live performance earns artists the right to call themselves true rockers, and to call their recorded music true rock music (authority). However, the aura of rock music is not only centered around how the work feels – It also incorporates the identity (authentic rock identity) of the artist who created or is creating the music.

But what about the theatre? How can a performance be authentic? Is not the whole premise of theatre that we are presenting an illusion to our audience – something that is not authentic – something that is not reality?

Jenn asked me if in the theatre we have to ‘pay our dues’ like in rock ideology – If we have to get the right training to be the real deal. We both agreed it’s not really the case. There are untrained actors who pop out of nowhere and aren’t regarded as inauthentic. To say that a conservatory training is necessary to render theatre authentic would inauthenticate all theatre that happens at Queen’s – We’re not at all a conservatory, and I would definitely not say I have never had an authentic theatre experience here.

Perhaps what authenticates theatre are the real-world implications of the act of performance? To borrow Jenn’s terminology of nested worlds, these would be the World A implications of the work.

Is the actor really sprinting across the stage, causing his heart to pound? Did he really drink the cyanide? Did he really die?

Obviously this is not the way the theatre operates – The actor cannot really die during the performance, because then he will only be able to do it once. What about the audience tomorrow night? But he really did run across the stage, and his heart really was pounding…

This reveals an interesting point – While yes, we are ultimately trying to create an illusion for our audience, the performance is not completely false. When the actor approaches another, she is really doing so. When she picks up a box, she is really doing so. When she hits another actor, sometimes she is really doing so. Since the World A actor body is implicated in the performance of the fiction, the World A actor body is undeniably affected. However, when the actor appears to kill the other actor, we know that she cannot possibly be doing so. All the same, we understand it to be part of the fiction.

Theatre necessarily is part reality and part fiction.

For theatre to be authentic, the fictional elements of the performance need to stay within the guidelines of our “willing suspension of disbelief” (a phrase popularly used within Drama, coined by Samuel Coleridge in Biographia LiterariaI, 1817).

I suggest that in the creation of the performance world, theatre artists shape the audience’s suspension of its disbelief. Depending on the parameters of the performance world, the audience (perhaps unconsciously) develops boundaries for what it will accept and what it will not accept as authentic during performance.

During a performance of a play that is set in a highly realistic setting, such as Soulpepper’s production of Kim’s Convenience, the audience needs only a low level of suspension of disbelief. For example, it comes to expect that all the props are real. The price gun actually puts stickers on cans. The cans of energy drink really do have liquid in them. The candy bars are really candy bars. The presence of real things on stage is so widespread in this production that if the audience were to suddenly see something not real – if Janet’s camera bag was actually a cardboard box tied around her with shoelace – it may see that aspect of the performance as inauthentic.

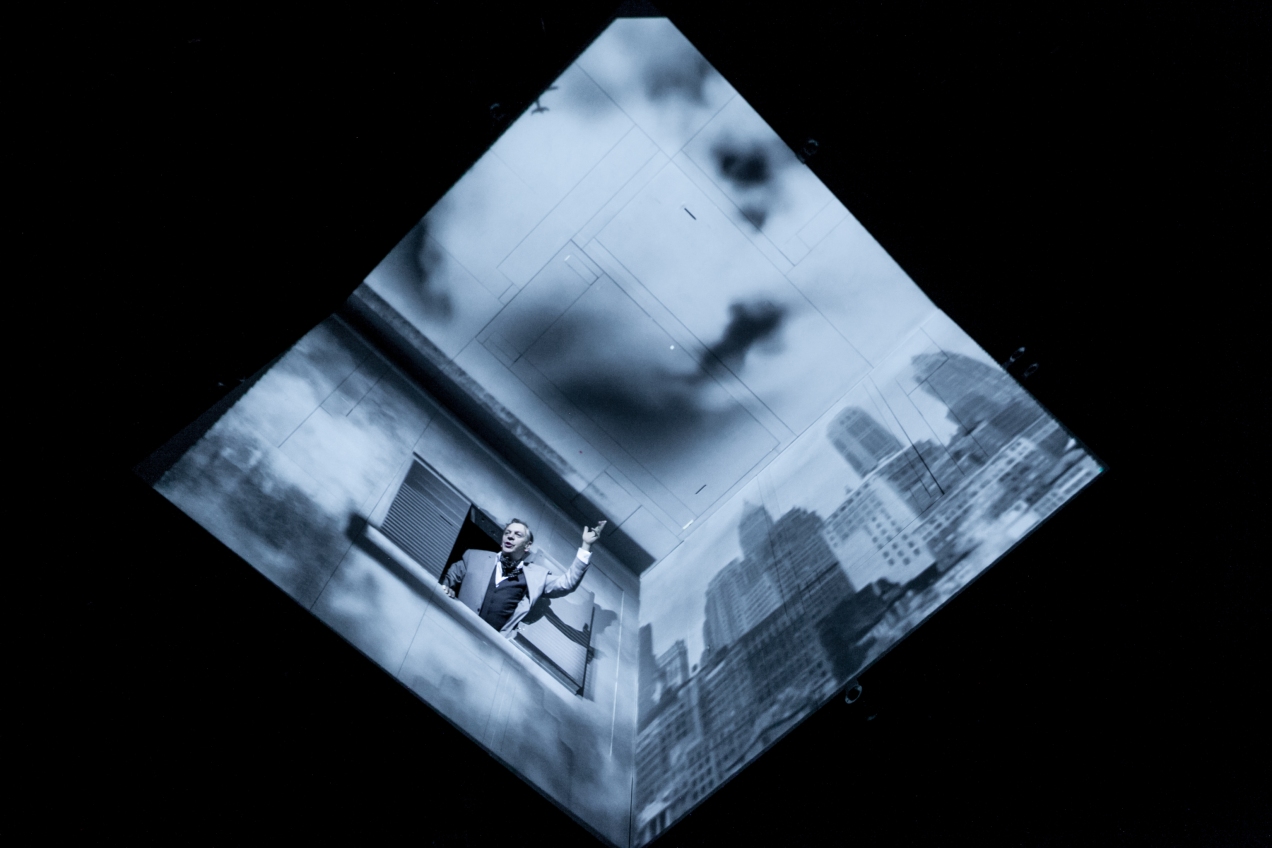

However, during a performance of a play produced in a highly stylized and unrealistic manner, such as Volcano Theatre’s production of A Beautiful View, the audience needs to employ a high level of suspension of disbelief. The set is bare, and props are few. The production uses a grey carpet, a radio, a small tent, some camping chairs, an artificial fig tree, some pillows, a teddy bear, and a funny hat. Right from the beginning, the audience is confronted with strange, cryptic movement in the actor bodies. All that is used to signify being at a rock concert are some coloured lights. The artists make no attempt to physically recreate a photorealistic rock concert setting, and the fig tree is evidently fake. However, I would not say that the production came across as inauthentic. The performance communicated its story and even changes in location well – And it certainly exhibited an aura – The feeling of the spectator while viewing a work of art. Though I was watching two people moving around an empty space, I did not feel like I was simply watching two people moving around an empty space. Somehow I was bearing witness to a work of art, and I could feel it.

It seems to me that the authenticity of theatre depends on the context in which the performance takes place. It is this context that directs the audience’s suspension of disbelief, defining what the audience will accept as authentic – And if the audience accepts the work as authentic, the work commands authority as art, and gains aura. While there is certainly something to be said for a skilled performance of a difficult act, I don’t think that authenticity in the theatre is necessarily about doing things for real. It’s about walking the line of suspended disbelief in the given performance context, and creating for the audience the true experience of watching something take place, despite the fact that they may know it is indeed not happening at all.

Image: Volcano Theatre’s production of A Beautiful View